Uno dei temi vitali per ogni economia è il ricambio generazionale, necessario per garantire futuro e continuità al sistema produttivo. Proprio a questo tema, ISMEA, l’Istituto di Servizi per il Mercato Agricolo Alimentare, ha dedicato il suo ultimo rapporto “Giovani e agricoltura” con cui ha analizzato e fatto il punto su numeri e trend della componente giovanile nel settore primario.

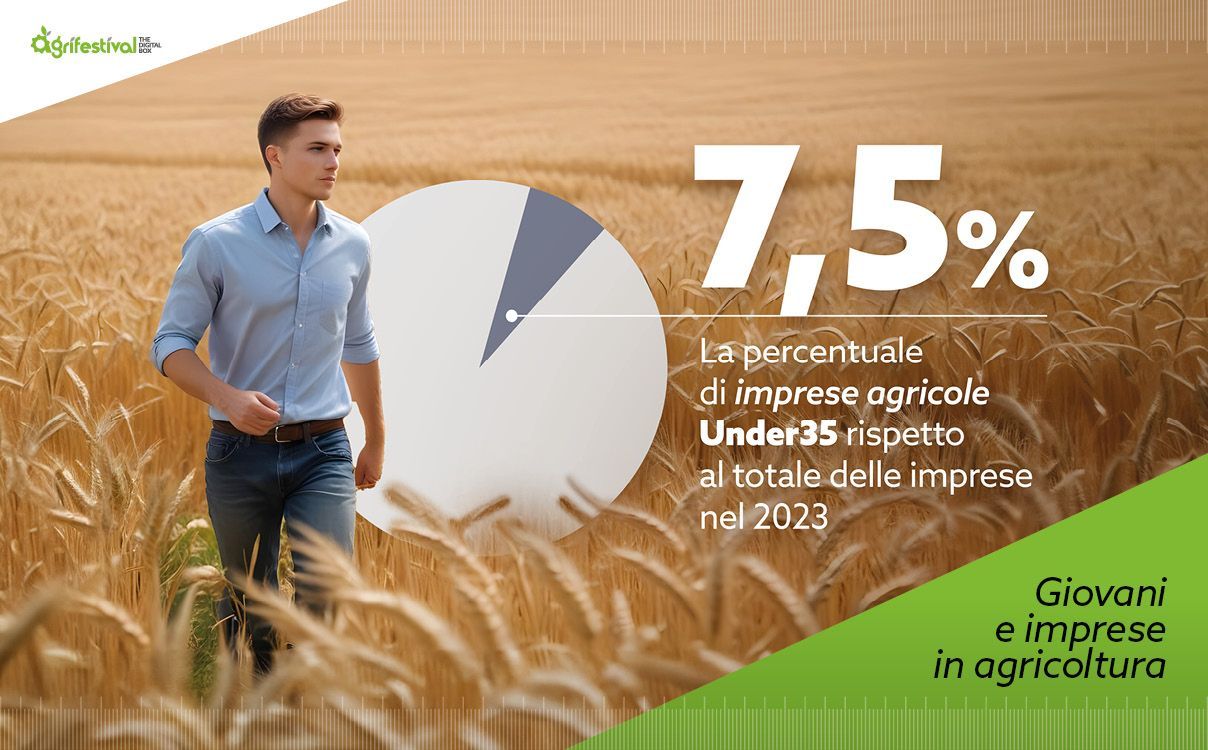

In generale, i numeri evidenziano ombre e luci. Partiamo dalla nota meno positiva. A fine 2023 le imprese agricole gestite da imprenditori under 35 sono 52.717 (su un totale di 703.975 imprese agricole), in calo dell’8,5% rispetto al 2018.

La flessione è comunque in linea con quella osservata per tutto il settore primario, con l’incidenza delle imprese agricole giovanili sul totale delle imprese agricole che, nel quinquennio 2018-22 rimane stabile al 7,7%.

Ma venendo agli aspetti più positivi occorre dire che l’andamento delle realtà agricole più giovani appare relativamente migliore rispetto a quello degli altri comparti produttivi.

Nel periodo 2018-23 le imprese agricole under 35 si sono ridotte molto meno, in termini relativi, rispetto alle pari età dell’industria alimentare, della ristorazione e dell’economia nel complesso, a dimostrazione di come l’agricoltura, nonostante tutto, mantenga un buon potere di attrazione di giovani leve.

Anche ampliando l’osservazione all’ultimo decennio, le imprese agricole giovanili registrano risultati più lusinghieri rispetto al complesso delle aziende agricole: la quota agricola sul totale è cresciuta sensibilmente per le under 35 (dall’8,3% del 2013 al 10,5% del 2023). In decisa crescita (+35,6%) le aziende giovanili di supporto all'agricoltura e successive alla raccolta (contoterzismo e prima lavorazione di prodotti agricoli), a dimostrare la crescente rilevanza delle attività remunerative connesse per le imprese condotte dai giovani imprenditori agricoli.

Se si passa poi a un’analisi per macro-aree territoriali dei dati, invece, è possibile notare come l’andamento di imprese agricole giovanili nel periodo 2018-23 sia stato diversificato nelle diverse zone del Paese: molto marcato al Mezzogiorno (-3.528 aziende, -11,4%) e al Centro (-1.144 imprese, -12,4%), decisamente più contenuto al Nord (-232 aziende, -1,3%).

Lo studio ISMEA propone poi un focus sui giovani nell’agricoltura europea, sulla base ai dati del Censimento 2020.

L’Italia è tra i paesi dell'UE con la quota di giovani agricoltori più bassa (pari al 9,3% considerando gli under 41 presi a riferimento dall'Istat), contro il 18,2% della Francia, il 14,9% della Germania e l'11,9% della media comunitaria.

Alle aziende junior si deve però la creazione del 15% del valore economico complessivo dall'agricoltura italiana (misurato nei dati censuari dal Prodotto Standard) e la ricchezza generata mediamente da un’impresa giovanile agricola italiana è pari a 82.500 euro (valore ben superiore a quella del settore, pari a 50 mila euro), pur posizionandosi sopra la media UE è inferiore a quella francese e tedesca.

Al contrario, il valore per ettaro delle imprese giovanili italiane, pari a 4.500 euro, è doppio rispetto a quello europeo e francese, ma superiore anche al valore medio unitario generato da un’impresa giovane tedesca e soprattutto spagnola.

Questo deriva dalla maggiore specializzazione dell’Italia in coltivazioni ad elevato valore aggiunto e di alto pregio (ortofrutta, floricoltura, viticoltura in primis).

In termini di occupati, invece, lo studio Ismea sottolinea come sia complesso condurre un’analisi sul tema senza tenere conto del fatto che l’offerta lavorativa in agricoltura è segmentata in diverse categorie, contraddistinte da livelli di istruzione, formazione e competenze molto eterogenei.

Da un lato c’è la manodopera meno specializzata, poco qualificata, spesso stagionale che risulta sempre più difficile da attrarre. Dall’altro lato l’innovazione tecnologica sta via via rendendo sempre più indispensabili, anche in agricoltura, figure professionali specializzate.

Ciò detto, nonostante nel 2022 l’agricoltura italiana, dopo tre anni di crescita, abbia registrato un calo del numero di occupati rispetto al 2021 (circa 40 mila in meno, pari a una riduzione del 4,2%), prendendo in esame l’andamento degli under 35, il settore ottiene una crescita di 8 mila unità su base annua, pari al 4,8%, raggiungendo le 183 mila unità.

Se si estende l’analisi degli occupati agricoli alla fascia di età fino a 40 anni, la crescita su base annua appare ancora più marcata (+6,7%). Con 290 mila lavoratori, gli occupati fino a 40 anni di età nel 2022 tornano ad essere circa un terzo dei lavoratori agricoli.

Analizzando la posizione professionale degli occupati agricoli giovani, si conferma la tendenza all’aumento dei dipendenti (+9,4% su base annua) a discapito degli indipendenti (-4,3% rispetto al 2021).

Nel valutare i dati sopra esposti occorre considerare che il coinvolgimento dei giovani nell’agricoltura in Italia risente dell’andamento demografico negativo e al generale invecchiamento della popolazione.

In Italia nel 2022 i giovani con età tra 15 e 39 anni sono 15,4 milioni, 2 milioni in meno rispetto al 2013 (-12%) e 4 milioni in meno rispetto a venti anni prima (-21%).

Il nostro Paese risulta anche essere il più “vecchio” dell’UE: nel 2022 il rapporto tra giovanissimi (fino a 15 anni di età) e anziani, che rappresenta un importante indice del ricambio generazionale, è in Italia pari solo al 53%, contro una media comunitaria del 71%. Oltretutto, le aree rurali italiane hanno subito un processo di progressivo spopolamento. Solo tra il 2018 e il 2022, la popolazione in tali territori si è ridotta del 3%, mentre è rimasta stabile nelle aree prevalentemente urbane. Il dato sullo spopolamento dei giovani (15-39 anni) è pari al doppio, raggiungendo il 6%.

Tra i fattori che accentuano l’abbandono delle aree rurali da parte dei giovani, vi è lo sviluppo ancora incompleto delle infrastrutture digitali e la carenza di servizi per la prima infanzia.

Questi elementi non riescono tuttavia a bilanciare aspetti positivi come la presenza di un diffuso patrimonio enogastronomico, culturale, artistico e ambientale, che può creare occupazione e coinvolgere le fasce più giovani della popolazione.

One of the vital issues for every economy is generational turnover, necessary to guarantee the future and continuity of the production system. Precisely to this theme, ISMEA, the Institute of Services for the Agricultural Food Market, dedicated its latest report "Youth and agriculture" with which it analyzed and took stock of the numbers and trends of the youth component in the primary sector.

In general, numbers highlight shadows and lights. Let's start from the less positive note. At the end of 2023, there were 52,717 agricultural businesses managed by entrepreneurs under 35 (out of a total of 703,975 agricultural businesses), down 8.5% compared to 2018. The decline is however in line with that observed for the entire primary sector, with the incidence of youth agricultural enterprises on the total agricultural enterprises which, in the five-year period 2018-22, remains stable at 7.7%.

But coming to the more positive aspects, it must be said that the performance of the younger agricultural realities appears relatively better than that of the other production sectors. In the period 2018-23, agricultural businesses under 35 shrank much less, in relative terms, compared to those of the same age in the food industry, catering and the economy as a whole, demonstrating how agriculture, despite everything, maintains good power to attract young talent. Even extending the observation to the last decade, youth agricultural businesses record more flattering results compared to all agricultural businesses: the agricultural share of the total has grown significantly for those under 35 (from 8.3% in 2013 to 10.5 % of 2023). There is a marked growth (+35.6%) in youth businesses supporting agriculture and following the harvest (contracting and initial processing of agricultural products), demonstrating the growing relevance of the related profitable activities for businesses run by young agricultural entrepreneurs. If we then move on to an analysis of the data by macro-territorial areas, however, it is possible to note how the trend of youth agricultural enterprises in the period 2018-23 was diversified in the different areas of the country: very marked in the South (-3,528 companies, -11.4%) and in the Center (-1,144 companies, -12.4%), decidedly more limited in the North (-232 companies, -1.3%).

The ISMEA study then proposes a focus on young people in European agriculture, based on data from the 2020 Census.

Italy is among the EU countries with the lowest share of young farmers (equal to 9.3% considering the under 41s taken as reference by Istat), compared to 18.2% in France, 14.9 % of Germany and 11.9% of the community average.

However, junior companies are responsible for the creation of 15% of the overall economic value of Italian agriculture (measured in census data by the Standard Product) and the wealth generated on average by an Italian youth agricultural company is equal to 82,500 euros (a value well above that of the sector, equal to 50 thousand euros), although positioned above the EU average, it is lower than the French and German ones.

On the contrary, the value per hectare of Italian youth enterprises, equal to 4,500 euros, is double that of the European and French ones, but also higher than the average unit value generated by a young German and especially Spanish enterprise.

This derives from Italy's greater specialization in crops with high added value and high quality (fruit and vegetables, floriculture, viticulture first and foremost).

In terms of employed people, however, the Ismea study highlights how complex it is to conduct an analysis on the topic without taking into account the fact that the job offer in agriculture is segmented into different categories, characterized by very heterogeneous levels of education, training and skills.

On the one hand there is the less specialized, low-skilled, often seasonal workforce which is increasingly difficult to attract. On the other hand, technological innovation is gradually making specialized professional figures increasingly indispensable, even in agriculture.

That said, despite the fact that in 2022 Italian agriculture, after three years of growth, recorded a decline in the number of employed compared to 2021 (around 40 thousand fewer, equal to a reduction of 4.2%), taking into consideration the trend of the under 35s, the sector achieved growth of 8 thousand units on an annual basis, equal to 4.8%, reaching 183 thousand units.

If we extend the analysis of agricultural workers to the age group up to 40 years of age, growth on an annual basis appears even more marked (+6.7%). With 290 thousand workers, those employed up to 40 years of age in 2022 will once again be around a third of agricultural workers.

Analyzing the professional position of young agricultural workers, the trend towards an increase in employees (+9.4% on an annual basis) to the detriment of self-employed workers (-4.3% compared to 2021) is confirmed.

When evaluating the above data, it must be considered that the involvement of young people in agriculture in Italy is affected by the negative demographic trend and the general aging of the population.

In Italy in 2022 there will be 15.4 million young people aged between 15 and 39, 2 million less than in 2013 (-12%) and 4 million less than twenty years earlier (-21%).

Our country is also the "oldest" in the EU: in 2022 the ratio between very young people (up to 15 years of age) and elderly people, which represents an important index of generational turnover, is only 53% in Italy, against a community average of 71%. Furthermore, Italian rural areas have undergone a process of progressive depopulation. Between 2018 and 2022 alone, the population in these territories decreased by 3%, while it remained stable in predominantly urban areas. The figure on the depopulation of young people (15-39 years) is double, reaching 6%.

Among the factors that accentuate the abandonment of rural areas by young people, there is the still incomplete development of digital infrastructures and the lack of services for early childhood.

However, these elements are unable to balance positive aspects such as the presence of a widespread food and wine, cultural, artistic and environmental heritage, which can create employment and involve the younger segments of the population.